Model United Nations has a fascinating history. It didn’t begin as “MUN” at all, and it certainly didn’t begin with perfectly timed motions and polished speeches! It started as a radical experiment: a group of students deciding that the best way to understand the world’s problems wasn't just to read about them, but to inhabit them.

More than a century later, MUN has become one of the world’s most widespread student diplomacy activities, with hundreds of thousands of students participating each year in schools and universities worldwide.

If you’re coming to NoviceNations 2026, or any of OG’s MUN events, you’re stepping into that story, and adding your voice to it.

1921–1945: before the UN, students were already practising diplomacy

The earliest “ancestor” of modern MUN is generally traced to a student-run League of Nations simulation at Oxford in 1921, often described at the time as an “International Assembly.”

The format was recognisable: delegates represented countries, followed procedure, and tried to solve international problems through structured debate. While they did not have the plastic placards or digital research tools we use today (often relying on simple nameplates and handwritten notes), the spirit of the simulation was identical to the modern version.

Within a couple of years, the idea had crossed the Atlantic. Sources commonly note that the president of the Oxford International Assembly, Mir Mahmood Ali, visited Harvard in 1922, and the first American International Assembly followed in 1923. Whilst not “big” in scale from the start, MUN was always global because students carried the concept with them and established it in new locations.

1947: The birth of the UN, and the "Model UN" we know today

After World War II and the founding of the United Nations (1945), student simulations shifted from modelling the League of Nations to modelling the UN itself. One widely cited milestone is the Swarthmore College conference in April 1947, often described as the first recorded conference explicitly called “Model United Nations.”

The parallels between that 1947 agenda and modern debate are striking. Whether the topic is disarmament or refugee crises, the core challenge remains the same: the difficult work of forging consensus among nations with competing priorities.

1968 onwards: MUN becomes a mainstream student experience

In the second half of the 20th century, MUN expanded rapidly, particularly at the secondary school level. A major landmark was the founding of THIMUN (The Hague International Model United Nations) in 1968, which demonstrated that high school conferences could operate with immense scale and professional influence.

This era transformed MUN from a series of isolated events into a global circuit. As conferences became annual fixtures with more consistent committee formats, it became an established expectation that the most effective way for students to learn diplomacy was by getting into the room and doing it. Within this global network, OxfordMUN has grown to become the largest high school MUN conference in the United Kingdom, serving as a primary hub for delegates looking to test their skills on a world-class stage.

1999: access and “who gets to be in the room”

As MUN grew, so did a major question: who actually gets to participate?

In 1999, UNA-USA launched Global Classrooms to help narrow the gap between well-resourced programmes and public schools with fewer opportunities. It was a turning point, because it shifted the focus from simply growing MUN to widening access. It wasn’t only about how many conferences existed, but about who could actually take part, and whether MUN could be realistic for students without easy access to funding and support.

2020: Resilience and the Digital Shift

While the MUN community had been gradually integrating digital tools for years, the real test of its resilience came in 2020. With global lockdowns and travel restrictions, conferences around the world, including OxfordMUN, moved online so that delegates could still meet, debate, and learn.

Online MUN was never a perfect replacement for being in the room together, yet it played an important role. It allowed debate to continue when in-person conferences weren’t possible, and it showed that the heart of MUN lies in the community and the skills it develops. Most importantly, it kept that momentum going until conferences could safely return in person.

Skills for the Global Stage

While MUN is a simulation, the skills it develops are entirely applicable to the real world. The structured debate and formal procedures used at conferences like OxfordMUN mirror the high-stakes environment of international relations. By following these rules, you learn far more than just global history. You master the art of public speaking, the nuance of policy drafting, and the grit required to negotiate under pressure. This is a training ground for real diplomatic thinking, designed to help you step into future leadership roles with confidence.

So where do you fit in?

If you’re a first-time delegate, it is easy to assume you’re arriving late to a tradition that everyone else already understands. The history of this movement suggests the opposite.

MUN has always been built by people who were once new. It is a story of students stepping into unfamiliar rules, learning a new vocabulary, and finding the confidence to realise they belong in the room. That is the tradition you're joining at NoviceNations.

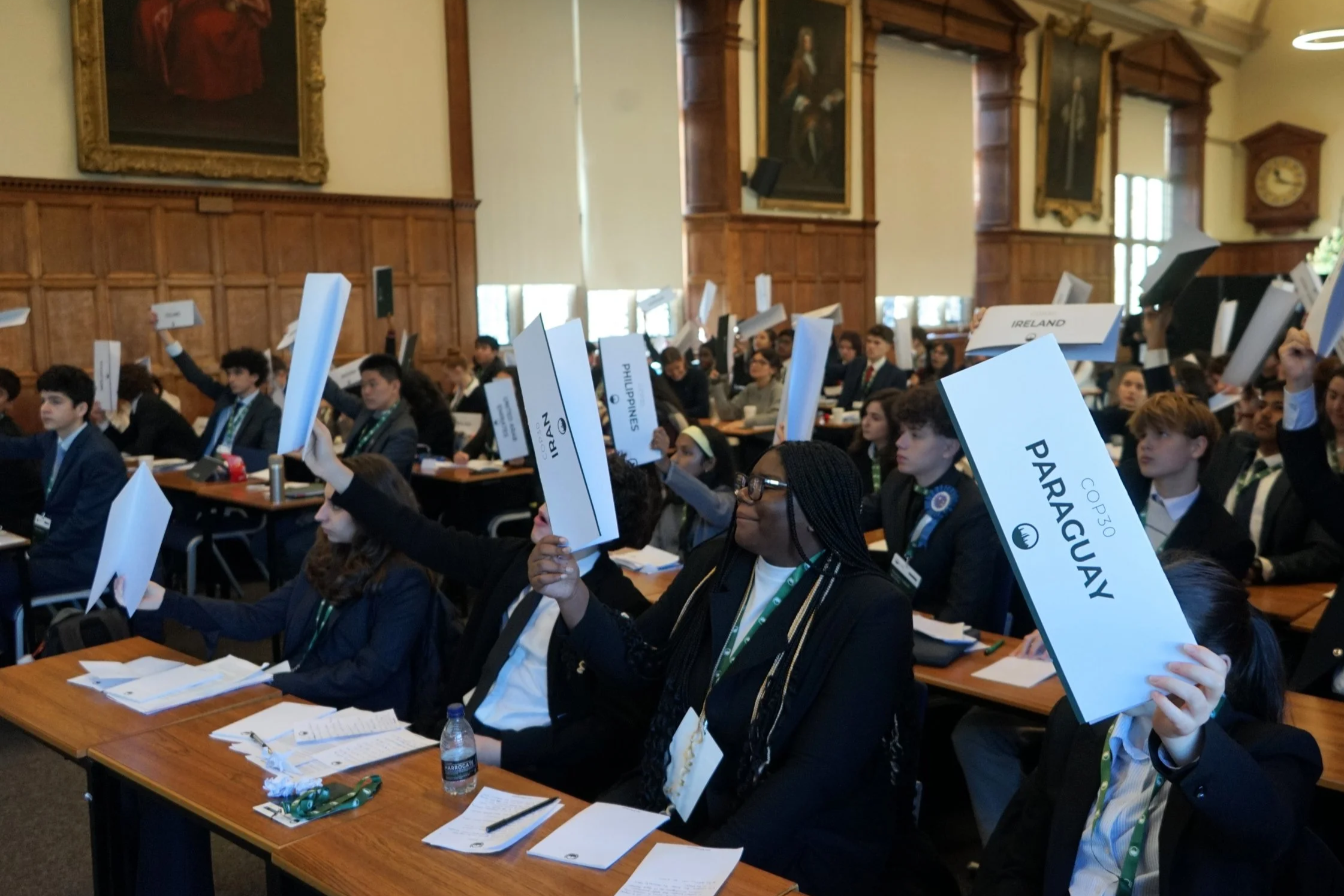

When you raise your placard for the first time, you’re doing more than just trying out a new activity. You’re taking your seat in a century-long experiment in global problem-solving, shaped through one speech, one negotiation, and one draft resolution at a time.